From blockade to war: The ethnic cleansing of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh

Genocide briefing

September 19, 2024

Co-publishers:

This report is also available in:

This report was commissioned by the Zovighian Public Office to serve as a public asset for Artsakhi Armenians and Nagorno-Karabakh.

Key findings:

- The ZPO has published a second edition of its open-source intelligence (OSINT) and geolocation report on the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh by Azerbaijan.

- The report presents detailed evidence refuting three consistent claims made by the Azerbaijani government through their state-led disinformation engine throughout the blockade.

- This second edition welcomes the Artsakh Union as a partner organization for this publication and has also been released in Arabic to contribute to the growing literature available on unconventional and conventional warfare in the Middle East, especially by Israel against the Palestinians of Gaza.

Keywords: Artsakh Nagorno-Karabakh; Lachin Corridor blockade; Artsakhi Armenians; conflict; humanitarian crisis; genocide; forced displacement; siege; Azerbaijan; Armenia

Opening letter

Dear reader,

Today marks one year since the violent military assault committed by Azerbaijan against the historic Artsakhi (Nagorno-Karabakh) Armenians, forcing the entire population to flee. This decisive expulsion came after nine months of an illegal blockade and comprehensive siege against the Artsakhi Armenian community, during which they were terrorized, starved, and stripped of many basic human rights and necessities.

At the start of the blockade, the Zovighian Public Office dedicated significant resources and efforts to study the blockade live and build a repository of evidence documenting crimes of war and genocide and crimes against humanity instigated by the Azerbaijani government.

This second edition of our open-source intelligence (OSCINT) and geolocation report on the blockade shows how Azerbaijan designed and executed the blockade to comprehensively expel Artsakhi Armenians from their ancestral homeland. Today, Artsakhi Armenian culture, heritage, and private property remain under siege and are being destroyed at alarming rates. Their leaders and citizens are illegally being held in arbitrary detention and are being subjected to torture, mistreatment, and sham trials. Nagorno-Karabakh remains ethnically cleansed of its indigenous Armenian population. The Artsakhi Armenian people cannot realize their right of return, a human right and legal responsibility that has been ordered by the United Nations International Court of Justice.

This new edition is now available in the Arabic language to provide Middle East analysts and diplomats with access to OSCINT data that is strikingly similar to the conventional and unconventional warfare tactics used by Israel against the Palestinians of Gaza. We note with great concern that Israel and Azerbaijan are military and trade partners with significant dependencies on each other’s expertise and resources.

We demand that Azerbaijan be held accountable for its many crimes against the Artsakhi Armenian people. We are disappointed by the inaction of the international community and are disgusted that Azerbaijan will be hosting COP29 in November of this year. This world order is a stark reminder that victims and survivors of genocide have few chances of wielding their power and living their lives on their own terms.

Respectfully yours, and with continued solidarity

Artak Beglaryan

A genocide survivor

Founder

Artsakh Union

Lynn Zovighian

Zovighian Public Office

Artak Beglaryan

Executive overview

On September 19, 2023, Azerbaijan launched a land and air

military offensive

on many Armenian towns and villages in Nagorno-Karabakh. (known as Artsakh by the Armenian people). The military victory was

decisive within only 24 hours. The attacks provoked a comprehensive

population-wide forced displacement

of the indigenous Armenians out of their centuries-old homeland.Since, almost the entire Artsakhi Armenian community has fled into Armenia, leaving vacant towns and villages ready for Azerbaijani settlement, as declared by Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev.

A year ago, on the Commemoration Day of National Leader Heydar Aliyev on December 12, 2022, Azerbaijani state-sponsored actors blocked the sole road on the Lachin Corridor connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia and the outside world, isolating 120,000 indigenous Armenians and instigating a human rights crisis in direct violation of international humanitarian law. On April 23, 2023, an official Azerbaijani military checkpoint was erected in the Lachin Corridor. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the only international humanitarian agency on the ground at the time, began to face tougher preconditions to negotiate their humanitarian vehicles and ambulances in and out of Nagorno-Karabakh. They lost all access to the Armenian population on June 15. The crisis aggravated into a full-blown humanitarian emergency with even more dangerously constricted local inventory. Health indicators were showing that starvation was fast-approaching. Psychological terror was rampant.

For this genocide briefing, the Zovighian Public Office appointed an open-source intelligence analyst to study a key research question:

Did Azerbaijan impose a blockade on the ethnic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh at the Lachin Corridor?

The findings of this report present a concerning pattern of steps and actions taken by Azerbaijan from December 12, 2022, to September 19, 2023, to strategically control the population and territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, while scaling an international credibility campaign.

During this period, the Government of Azerbaijan consistently made three claims to justify their policies and positions. Their version of events denied the suffering of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh and deemed the blockade a fabricated narrative by local representatives to appeal for the support and solidarity of the international community and derail peace talks.

This paper is structured around these three claims to examine them openly and in depth. As such, this paper is a repertoire of methodical evidence that answers this research question, refuting the claims made by the Government of Azerbaijan. The Methodology section details the approaches taken and the principles adopted to conservatively study and present key findings.

Claim 1: There was no road closure and no blockade, and the protest at the Lachin Corridor was an independent grassroots movement of civil society actors who took a stand against ecoterrorism committed by Armenian mining activities.

Claim 2: Azerbaijan had the right to erect a checkpoint at its border with Armenia on the basis of territorial integrity and security.

Image 2

Military personnel standing by the Azerbaijani military checkpoint at the Lachin Corridor road

Source: International Crisis Group

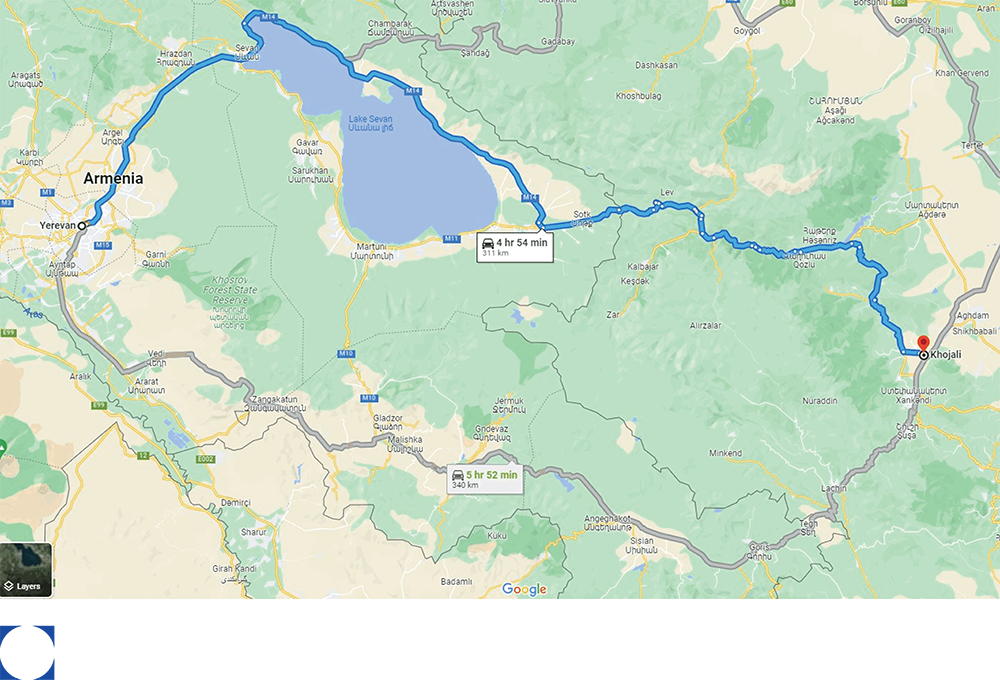

Claim 3: There was no blockade because alternative roads could be used aside from the Lachin Corridor, in particularly the Aghdam-Askeran Road.

Image 3

Potential roads shown on Google Maps for further investigation

Source: Google maps

To evaluate these insistent claims made by multiple government officials and media outlets in Azerbaijan, it was important to verify whether Nagorno-Karabakh was effectively put under blockade and siege. This was done by geolocating both the Lachin Corridor road closure and the military checkpoint, and studying the existence of any alternative route(s) that could be safely and unconditionally used by Armenian civilians and humanitarian agencies.

This investigation demonstrates that over a ten-month period, calculated pressure points and power plays by Azerbaijan instigated multi-dimensional emergencies against the indigenous Armenian population, from existential and humanitarian catastrophes to economic, geopolitical, and self-governance crises. Azerbaijan also initiated an information blockade and introduced rhetorical cards and misinformation campaigns to help prompt their strategic ultimatum to the historic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh: forced population transfer or forced integration, both on Azerbaijani terms. On September 19, 2023, Azerbaijan launched an extraordinary full-scale military assault into Nagorno-Karabakh and succeeded in fully displacing all ethnic Armenians, disarming the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army, and dissolving the public institutions of the autonomous government. This investigation examines the disempowerment strategies that prepared the ground for this offensive and decisive victory.

Methodology

In the first month of the Lachin Corridor blockade, the ZPO

commissioned a series of multidisciplinary research missions to closely study the means of oppression and violence used by Azerbaijan against the indigenous Armenian people of Nagorno-Karabakh. These investments in research aim to equip stakeholders in the diplomatic, legal, and scientific communities with a traceable, replicable, and testable thought process.

Commissioned researcher

The ZPO commissioned an open-source intelligence analyst (name withheld) for this research mission.

Research design

Against limited scientific and verified public documentation, this research mission employed geolocation and open-source intelligence (OSINT) methods using a conservative methodical approach with fact-checked data inputs.

This investigation studied three official claims made by the Government of Azerbaijan between December 2022 and September 2023 that there was no blockade, because:

- An independent grassroots movement closed the Lachin Corridor road;

- The checkpoint was based on the right of territorial integrity; and

- Alternative routes could be taken.

To investigate the Azerbaijani claims, this research mission was designed with six research objectives and one primary research question.

Research objectives

- Develop a situational awareness of and around the Lachin Corridor and Nagorno-Karabakh;

- Understand the geopolitical and power dynamics that contributed to the implementation of a comprehensive ten-month territorial, population, and informational control of Nagorno-Karabakh;

- Investigate the strategies adopted and implemented by the Azerbaijani Government and other actors at the Lachin Corridor that affected the security, quality of life, and forced displacement of the ethnic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh;

- Accurately locate the road closure and checkpoint at the Lachin Corridor;

- Identify and examine feasible alternative roads to the Lachin Corridor road that could be trusted as safe and free to use; and

- Study how Azerbaijani state rhetoric evolved and enabled oppressive strategies and actions

Research question

Did Azerbaijan impose a blockade on the ethnic Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh at the Lachin Corridor?

Data collection

Prior to commencing this research mission, a search was conducted for any geolocation studies and OSINT in the context of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh and could not find a study that situated the blockade and military checkpoint in space and time. Given the complexities of the history of conflict and violence in Nagorno-Karabakh, and that the blockade and military

assault

were the last infliction points before the comprehensive forced population transfer, adopting rigorous geospatial methodologies using OSINT protocols was necessary.

Input data was solely open-source, based on verifiable evidence. All multimedia used were found in the public domain, notably:

- Search engine: Google

- Satellite imagery platforms: Google Earth and Google Maps

- Social media platforms: Facebook, Instagram, X, and Telegram

Except for satellite imagery and citizen images posted on Google Maps and Google Earth, all collected multimedia was authored by Azerbaijani sources, especially government, media, and citizens. The decision to collect data through Azerbaijani sources was important, not only to study the content, but also to assess the significance of every piece of information that was made public by each author. OSINT protocol relied mainly on manual methods. No automated tools were required for this research.

Given the deeply politicized, inflammatory, and convoluted situation in Nagorno-Karabakh, several cautionary measures needed to be taken to achieve credible standards of integrity and evidence. The research team regularly conducted iterative stress-testing and ensured sources were thoroughly checked. Information was also not taken at face-value and was consistently approached with humility, respect, and recognition of any expertise limits.

Research ethics

The images and videos used in this report were posted publicly on social media or other websites. There was no use of sock puppets to intrude into the social media accounts of participants that have been made private since the start of the blockade.

Data security and protection

All open-source information has been archived with a dating protocol, should any used information or sources be removed or altered after this research effort.

Language

The Soviet-time official names of roads, cities, and regions in Nagorno-Karabakh are used, which are internationally referenced by the United Nations (UN), including the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the Council of Europe, in strong recognition of the violence associated with erasure or exclusion of ethnic names.

Study limitations

OSINT limitations relate to the practical aspects of capturing online evidence, especially evidentiary issues associated with websites and the reliance on self-reported and publicly shared information. Any uncertainty in geolocation results is estimated to be below 50 meters of radius.

Opportunities for further research

This foundational knowledge can support future research endeavors on Nagorno-Karabakh, equipping human rights lawyers, diplomats, and activists with findings and methods to continue activating accountability mechanisms and live monitoring the South Caucasus.

Claim 1: There was no road closure or blockade

On December 12, a group of Azerbaijani citizens disrupted the transit route between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. Azerbaijani pro-state media outlets referred to the demonstrators as environmental activists who were protesting alleged illegal mining by Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh and the transportation of the mined minerals through the Lachin Corridor into Armenia.

Many so-called protestors posted on their social media accounts photos and videos of their movements, activities, and endorsement of this effort. Using their social media accounts, it was possible to map the exact GPS coordinates of this so-called protest through visual interpretation of the images and their geolocation. The self-posted social media content also provided detailed insights into the itineraries, demographics, and motivations of the participants.

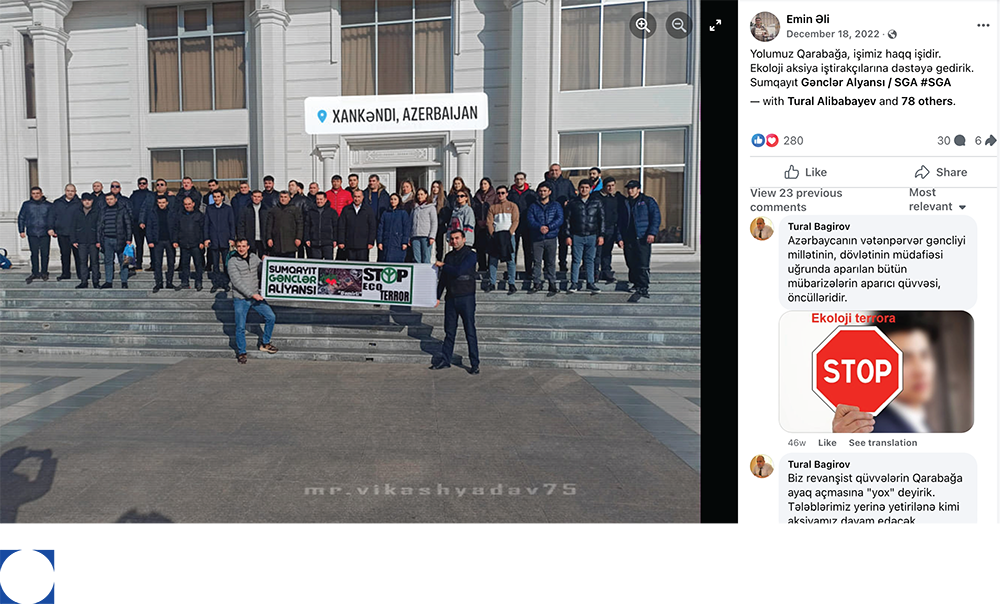

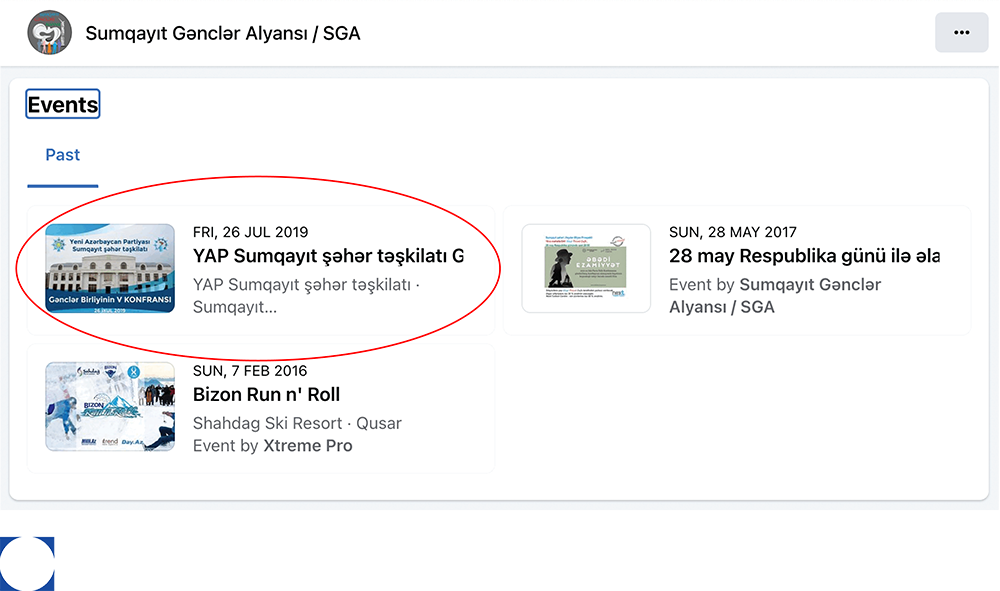

The journey to the alleged eco-activist protest

One image

posted on Facebook shows 42 individuals posing for a photo on stairs in front of a white building and holding a sign that reads: “Sumqayit Gənclər Aliyansi Stop Eco Terror.”

This post was accompanied by a caption in Azerbaijani with the direct translation in English below:

Yolumuz Qarabağa, işimiz haqq işidir.

Ekoloji aksiya iştirakçılarına dəstəyə gedirik. Sumqayıt Gənclər Alyansı / SGA #SGA

Our way to Karabakh, our work is the work of justice.

We are going to support the participants of the environmental action. Sumgait Gənclər Alyansı / SGA #SGA

Image 4

Alleged eco-activists pose for a group photo holding a sign that reads 15 “Sumqayit Gənclər Aliyansi Stop Eco Terror”

Source: Facebook

Now that a suspect building was identified and more photos of it could be gathered online, a detailed comparative analysis was performed, resulting in a complete match, including the windows (blue circles, green circles), door head (light blue circles), columns (burgundy circles), tiles (red circles), stairs, and outdoor spaces. A comparison with satellite imagery as seen in Exhibit 1 confirmed the building to be that of the New Azerbaijan Party in Sumqayit at GPS coordinates: 40.57782, 49.68808.

Exhibit 1

Three images of the New Azerbaijan Party building in Sumqayit with identifying visual elements highlighted

Sources: Unikal.az (top image); Xeberle.com (middle image);

Google Maps (bottom image)

The journeys of some of the alleged protestors were traced using two road signs that appeared on two different Facebook video posts. The first video was posted on December 13 with a caption already indicating the city of Shushi as their destination:

“Together with more than 200 #Azerbaijani volunteers, including Agrarian Development Volunteers, we are going to #Shusha road to demonstrate our civic position for #Khankendi. #Khankendi #KarabakhisAzerbaijan”

Despite the illegibility of some of the digits on the road sign due to the image quality in the video, it was still possible to accurately geolocate the road sign at GPS coordinates: 40.29555, 49.75161, as shown in Exhibit 2. In Step 1, a clearer image of the same road sign was found to narrow the target area to the Baku-Qazax Highway. In Step 2, a satellite image of part of the Baku-Qazax Highway revealed the matching green patch of pine trees (light blue circles) facing the wall serrated with columns (red circles). In Step 3, the Street view feature on Google Maps showed the road sign (green circles) in its identified location, and lastly in Step 4, the geolocation of the initial image and road sign was confirmed.

The chokepoint

The geolocation of the alleged eco-activist protest started with collecting 10 video frames and images containing visual landmarks that suggested a protest in action.

A video that was uploaded on Google Maps on December 12 with a panoramic view of the protest helped to confirm the co-location of the below-mentioned images. This was done by cross-linking the following visual elements as seen in Exhibit 3: a metallic signpost (green circles), a striped boom bar (burgundy circles), a road barrage (dark blue circles), a rocky mountain (beige circles) with a forest at its flank (dark green circles), a transmission tower (blue circles), and a military tent (red circles).

Exhibit 3

Matching characteristics between the video and the images proving the co-location of the images

Sources: Google Maps; Facebook (Far left frame; middle left frame; middle right frame; far right frame; far left image; middle left image; middle right image; far right image)

Four of the images were geotagged as Shushi on their respective social media platforms, but without further location-specific details. With the help of satellite imagery, as shown in

Exhibit 4, it was possible to establish that the following visual elements intersected at the southwest entrance of Shushi, with GPS coordinates: 39.75213, 46.72901: a police station (green circles), Shushi sign (burgundy circles), a rocky mountain (beige circles), a transmission tower (blue circles), and a guardhouse (red circles).

At this location, Azerbaijan meets the Lachin Corridor road through a parallel road called

Fuzuli-Shushi Highway, translated as “Victory Road,” that was specifically constructed to link Shushi to the rest of the country. The two roads, Fuzuli-Shushi Highway on the Azerbaijani side, and the Goris-Stepanakert Highway (Lachin Corridor road) seem to be divided by a metal separator.

Exhibit 4

Geolocation of the alleged eco-activist protest by satellite imagery and social media

Sources: Google Maps; Facebook (Top left image; top middle image; top right image; bottom left image; bottom middle image; bottom right image)

The crowd that gathered at the so-called protest were not all civilians. Two distinguished military uniforms were identified on the ground, as shown in Exhibit 5. The first distinguishable military contingency was identified as the Russian peacekeeping forces, given the Russian flag and their Cyrillic abbreviation “MC,” short for Mirotvorcheskiye Sily. They were part of the implementation of the Trilateral Agreement that ended the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War / 44-Day War of 2020. The second military group was identified as the Internal Troops of Azerbaijan under the Ministry of Internal Affairs from their Finnish M04 Hellekuvio desert camouflage. Their high-cut helmets (red circles) favor them to be within the Special Forces of this unit. Their location is observed to be restricted to Fuzuli-Shushi Highway, and technically not on the Lachin Corridor road. The presence of Azerbaijani military elements was reported by international media.

Exhibit 5

Identification of military units present at the alleged eco-activist protest: Russian peacekeeping forces and Azerbaijani Internal Troops

Sources: Le Monde; fareastmilsim.com; Camopedia.com

This conglomeration of factors is presented to the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh as a fait accompli; right in the middle of the Goris-Stepanakert Highway (Lachin Corridor road), a human crowd of the so-called eco-activists stand by tents that were erected on the pavement. They are surrounded by Russian peacekeeping forces and Azerbaijani Internal Troops, as seen on Image 6.

Image 6

Alleged eco-activists blocking the Lachin Corridor road, flanked by Russian peacekeeping forces and Azerbaijani Internal Troops

Source: Facebook

This conformation created a physical obstruction and hostile space on the Lachin Corridor, evoking physical unsafety and psychological terror for any Armenian traveler. With no mines in the immediate vicinity, the choice to block this particular route to protest alleged Armenian mining activities in the region remains unexplained and unjustified.

Image 7

Halted car traffic next to road sign with passengers standing outside their vehicles

Source: First News

Another image that was posted on First News on December 15, shows blocked traffic in one direction of a two-way road, with a few passengers who have stepped out of their vehicles. The geolocation exercise for this image aimed to specify the region in which this seemingly exceptional traffic obstruction had occurred. A road sign reads the name of three cities and the distances to reach each one.

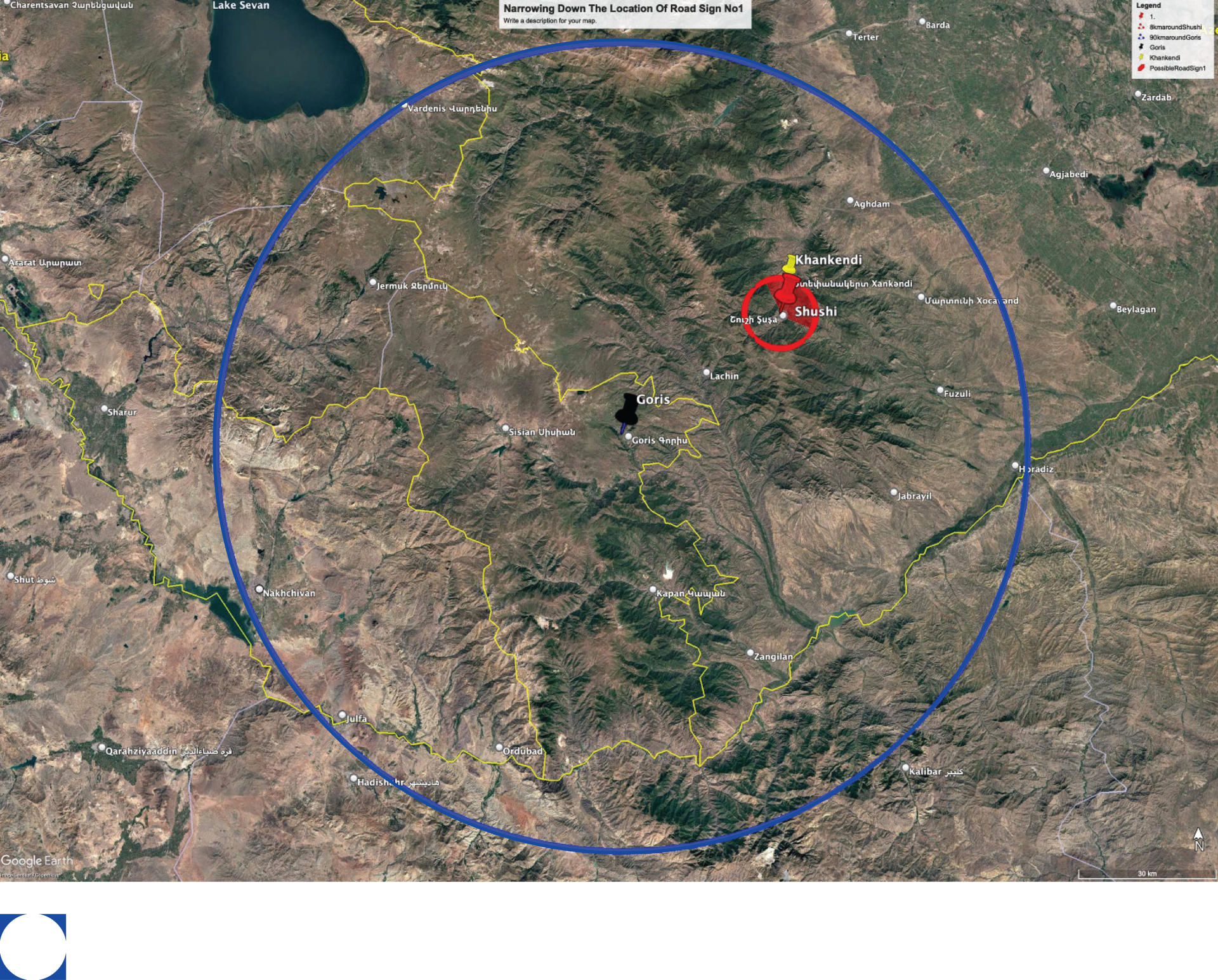

Using the information inscribed on the road sign, two circles with radius 90 kilometers (blue circle) and eight kilometers (red circle) were drawn around Goris and Shushi respectively, as shown in Exhibit 6. This narrowed the region of interest to a small area inside the red circle.

Exhibit 6

Geolocation of road sign with satellite imagery using the cities and distances inscribed

Source: Google earth

A set of useful images of the same road sign were obtained by using Reverse Image on Google, which situated the road sign near identifiable landmarks, as seen in

Exhibit 7. The top right image shows Russian peacekeeping troops and two of their tanks, indicating their earlier deployment to this location. Using satellite imagery, the car traffic was geolocated at a curve on the Lachin Corridor road driving south from Stepanakert to Shushi at GPS coordinates: 39.79706, 46.76712. Exhibit 7 highlights the matching curve, the brown brick roof (green circles), green oval garden (dark blue circles) flanked by an entrance and exit (red circles, burgundy circles), and two houses on top of a hill (blue circles, light blue circles).

The road traffic upstream of the alleged eco-activist protest clearly shows a physical obstruction. Travelers from Nagorno-Karabakh who had once experienced free movement became disconnected from Armenia.

Exhibit 7

Geolocation of road sign with satellite imagery using the cities and distances inscribed

Source: Google Earth; Instagram; Civilnet

The imposition of a blockade marked the beginning of a multi-faceted strategy with various tactics from an alleged eco-activist protest to the establishment of a military checkpoint at the entrance of the Lachin Corridor road. The alleged protest was weaponized against the indigenous population of Nagorno-Karabakh, amplified by intense high ethno-nationalistic and anti-Armenian sentiments.

The free-for-all participation and presence of different actors, some with political and military mandates as per the Trilateral Agreement of 2020, and others with ethno-nationalistic and governmental mandates, created a concentrated chokepoint where law and order became co-governed by power and agents of power. Together, they clearly closed the Lachin Corridor road and offered no recourse for humanitarian convoys and Armenian travelers to enter and exit freely, safely, unconditionally, and uninterrupted.

Its location, between the capital Stepanakert and Armenia, specifically at the southwest entrance of Shushi, afforded the crowds tactical protection because of the Azerbaijani National Internal Troops who began to build a military presence there following the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War / 44-Day War of 2020.

Claim 2: The right to erect a checkpoint

The weaponized protest sustained a humanitarian crisis for over five months before a disruptive change in tactic. On April 23, Azerbaijani military units crossed into the Lachin Corridor and established a military checkpoint at its entrance, formalizing territorial control for the first time since the supposed end of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War / 44-Day War of 2020. On April 28, months into the alleged eco-activist protest, the so-called protestors announced that they were withdrawing from their location until further notice.

Multiple reports indicated the location of the checkpoint near a bridge above the Hakari river. Satellite imagery was used to trace down the river near the border of Armenia and Azerbaijan, which led to a suspected location as shown in the middle image of

Exhibit 8. At the time of writing this report, this image was the latest available on Google Earth for this location, dated April 2022. It showed the bridge still under construction. A few hours after the installation of the checkpoint, Armenian First Channel News obtained a more

recent satellite image

(bottom image) that showed the construction of the bridge was almost completed. The checkpoint was geolocated at GPS coordinates: 39.565794879554126, 46.571236929402545 by comparing the two satellite images with a screen capture from a

video

posted on Twitter (top image). The matching features include the rocky striped hill (burgundy circles), riverbanks (beige circles), curved sandy path (green circles), main road crossing the bridge (red lines), and rectangular pitch (blue circles).

Exhibit 8

Geolocation of the checkpoint using two satellite images and one screen capture

Sources: Armenian First Channel News (bottom image); Google Earth (middle image); Twitter (top image)

With the checkpoint, Azerbaijan militarized and institutionalized a comprehensive siege of Nagorno-Karabakh under the cover of international law and state rights to territorial integrity, effectively responding to global pressure to respect international humanitarian and human rights law by presenting a counter-commitment to international law centered on sovereign rights.

Azerbaijan demonstrated that they were prepared for the long game; as soon as international community demands to open the Lachin Corridor escalated, Azerbaijan switched the emphasis from the need to save the environment to the right to ensure territorial integrity and end the so-called smuggling of weapons. This official rhetoric was neither held accountable at any point of the blockade nor following the complete takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Azerbaijani military presence was now no longer restricted to the outskirts of Shushi on Fuzuli-Shushi Highway (Victory Road). The deployment of the Azerbaijani Border Service marked the first formal military presence on the Lachin Corridor road.

While the Trilateral Agreement had already been weakened by the alleged protest, it was now clearly violated and nullified by the checkpoint.

On the ground, this institutional checkpoint solidified territorial, population, and information control. It opened the opportunity for state arrests of ethnic Armenian citizens and representatives. Following the September military assault, the checkpoint became the ultimate gatekeeper, acutely aggravating psychological terror against ethnic Armenians who fled Nagorno-Karabakh.

The checkpoint may also be the stronghold that ring fences the right of return for those who wish to come back.

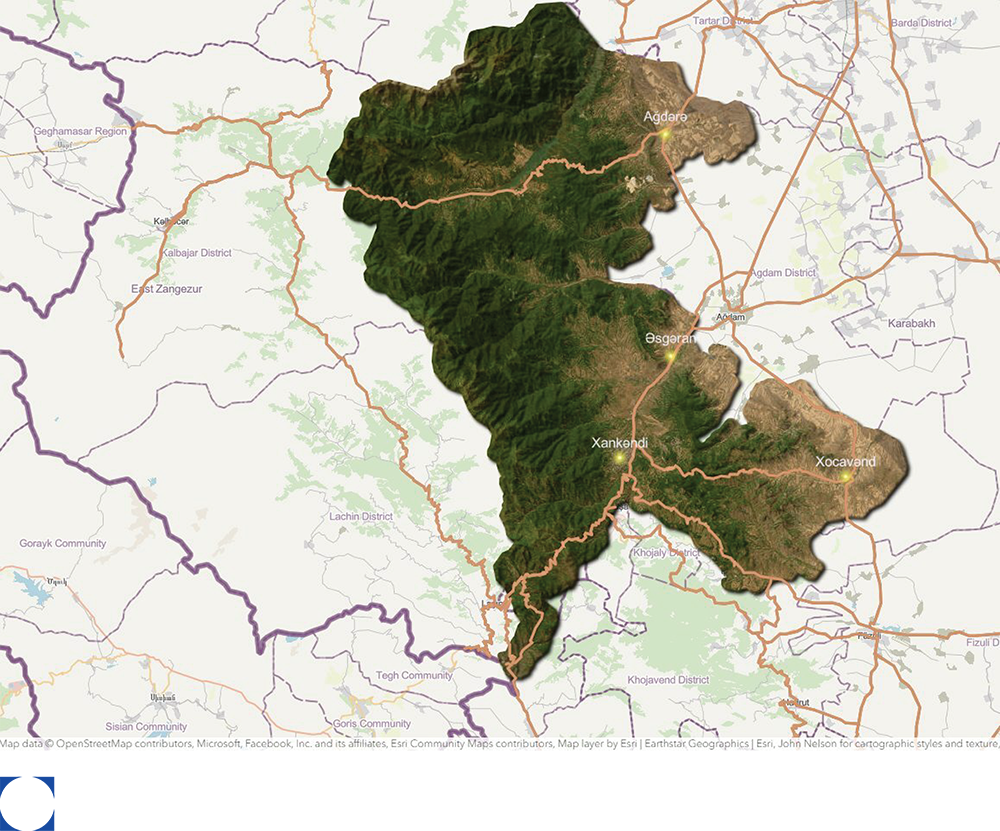

Claim 3: There were alternative routes

With the obstruction of the Lachin Corridor Road confirmed, the most direct way to verify whether the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh had an alternative road to Armenia was to use Google Maps. Azerbaijan benefited from the humanitarian crisis they caused by proposing to make it their responsibility to supply aid to the population to further build territorial and population control.

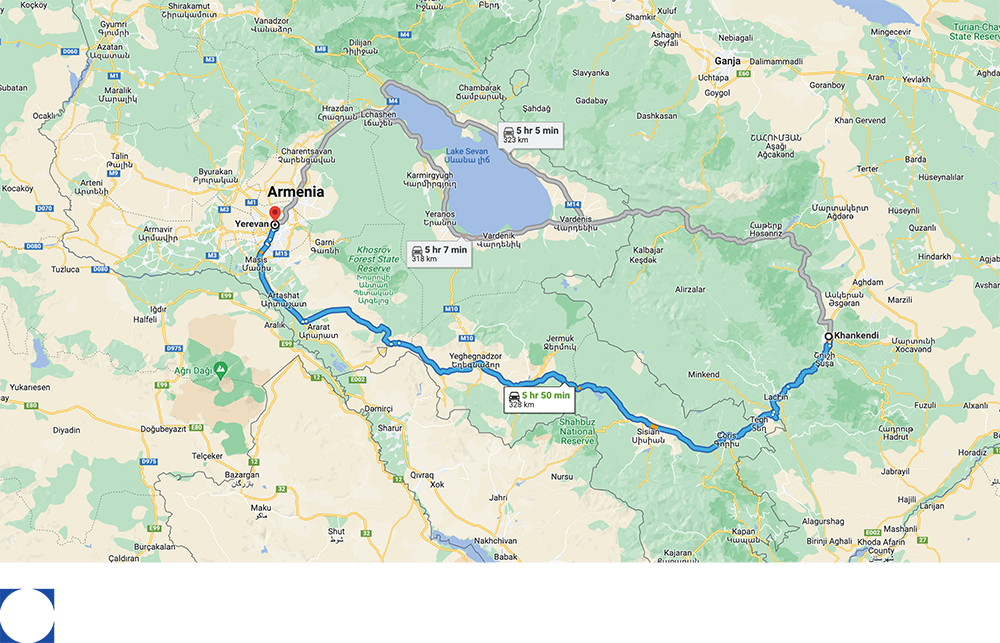

The simplest and most direct way to search for alternative routes was to ask Google Maps for directions. On September 13, at 21:24, a directions query from Stepanakert to Yerevan (an Armenian destination with an approximate similar latitude to that of Stepanakert) was performed, as shown in Image 8. This search returned two possible border crossings: the Berde-Istisu-Kelbecer Yolu with a travel time of 5 hours and 5 minutes by car for 323 kilometers through the Sotk Pass to the M11 in Armenia, and the Goris-Stepanakert Highway (Lachin Corridor road) with a travel time of 5 hours and 53 minutes by car for 328 kilometers through the Lachin Corridor.

Image 8

Direction query on Google Maps from Stepanakert / Khankendi to Yerevan

Source:

Google maps

This theoretically meant that there was another road driving northwest and connecting Stepanakert to Armenia. This alternative border-crossing through the Sotk Pass seems to have been proposed by X account @DataQarabag a few days into the start of the alleged eco-activist protest, as

posted on their map

and shown in Image 9.

Having demonstrated the various ways by which Azerbaijani actors have blocked the free movement on the Goris-StepanakertHighway (Lachin Corridor road), there was still the need to verify the feasibility to drive through the Sotk Pass from Azerbaijan into Armenia.

The Sotk Pass seemed opened prior to October 2019, as shown in

Image 10. The most recent satellite imagery on Google Earth, dated July 2023, as shown in

Image 11, reveals military barricading with an artificial sand hill on the Armenian side and multi-layered road barriers on the Azerbaijani side.

Image 10

Historical satellite imagery of the Sotk Pass in 2019

Source: Google Earth

Image 11

Current satellite imagery of the Sotk Pass in November 2023

Source: Google Earth

While there might have been theoretical choices for travel, the aim of this geolocation analysis was to understand whether any of those options were feasible and could both guarantee freedom and safety of movement while respecting the personal and cultural ties between two different populations on the other hand. With the Sotk Pass blocked to all passage by vehicle, the two transborder roads were proven to be inaccessible and all other roads departed from Azerbaijan.

The Lachin Corridor road remained the only possible connection by land between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia.

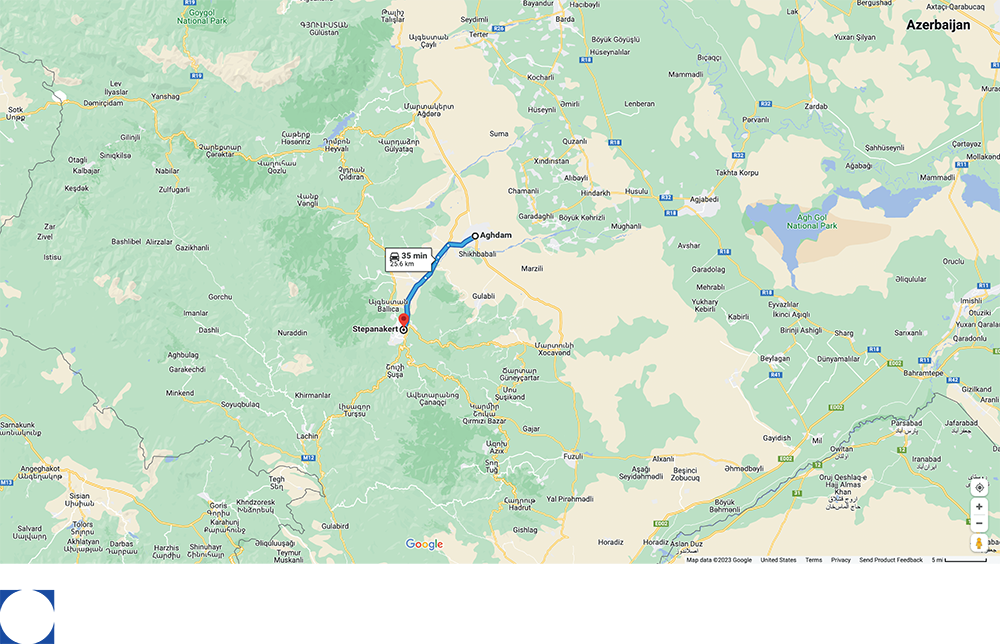

Image 12

The Aghdam-Askeran Road on Google Maps

Source: Google Earth

On July 14, the Azerbaijani Minister of Foreign Affairs Jeyhun Bayramov proposed the Aghdam-Askeran Road to the ICRC to meet “the needs of Armenian residents.” As observed in Image 12, Aghdam cuts the geographic ties between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia.

Rather than protecting a free connection between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, the focus on the right of free movement of people and goods was relegated to just the right of access to aid, a rhetorical muddling that lasted throughout the blockade.

Not only did this proposal violate Clause 6 of the 2020 Trilateral Agreement, but it also presented a forced integration strategy where ethnic Armenians would be fully dependent on Azerbaijani aid, the vital lifeline of the Lachin Corridor road would be nullified, and the independence of the autonomous political governance of the Republic of would be destabilized.

Building barricades while claiming to propose a safe future of integration exposed what life in Azerbaijan would look like if ethnic Armenians held onto their homeland.

Conclusion

On August 7, the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR)

called upon

Azerbaijan to immediately restore free movement on the Lachin Corridor road. On August 16, the United Nations Security Council held a session on the humanitarian crisis and also

called for

the reopening of the Lachin Corridor. Azerbaijan once again became globally known as the South Caucasus neighborhood bully that does not want to meet international human rights standards. Under pressure, the Azerbaijani Government needed to evolve its strategy, while making sure Nagorno-Karabakh did not become its Achilles heel.

On September 12, European Council President Charles Michel acknowledged the Aghdam-Askeran Road as an option for humanitarian delivery, but still called for the reopening of the Lachin Corridor road.

Azerbaijan was able to leverage its confounded rhetoric to build diplomatic credibility with the international community, without needing to give back any negotiating power or backtrack on any of the claims investigated in this report.

The few weeks that followed appeared to show hints of a possible easing of the blockade. On September 17, an agreement was announced between the Azerbaijani Government and the autonomous government of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh to use both the Aghdam-Askeran Road and Lachin Corridor road for humanitarian assistance. The announcement was positioned as a win by Azerbaijan on their negotiations with Artsakhi leaders on multiple Azerbaijani media outlets. On September 18, humanitarian aid was transported into Nagorno-Karabakh through the Aghdam-Askeran Road.

The next day, on September 19, Azerbaijan launched a military operation into Nagorno-Karabakh, which the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense positioned as “local anti-terror measures” to uphold the Trilateral Statement of 2020 and realize a series of strategic objectives:

“[…] suppress large-scale provocations in the Karabakh economic region, to disarm and secure the withdrawal

of formations of Armenia’s armed forces from our territories, neutralize their military infrastructure, provide the safety of the civilian population returned to the territories liberated from occupation, the civilians involved in construction and restoration work and our military personnel, and ultimately restore the constitutional order of the Republic of Azerbaijan.”

This represented the single largest and most direct territorial takeover since the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War / 44-Day War of 2020. The land and air military offensive resulted in a comprehensive capitulation, annihilation, and reconstitution of Nagorno-Karabakh. It was a decisive success.

While the road closure and checkpoint created conditions that significantly endangered an entire indigenous population, which according to International Criminal Court Founding Chief Prosecutor Luis Ocampo,

triggered Article IIc

of the Genocide Convention, the military offensive fueled these conditions to achieve total ethnic cleansing. Since, multiple crimes of war and genocide continue to be studied and verified: the

complete forced population transfer

of all historic ethnic Armenians out of their homeland;

mass murders, cases of

torture; the

arbitrary detention

of civilians and representatives; the

pillaging

and

takeover

of villages and cities; and the

destruction of cultural heritage. Azerbaijan has yet to be held accountable for any of these crimes.

Now with the data made available in this report, it is evident that an unconventional war began on December 12, 2022 and climaxed into a conventional war on September 19, 2023, with resounding victories at every step of the way.

Several hybrid and conventional warfare tactics were used to achieve multiple objectives of community destruction and erasure in only a ten-month period. The September military offensive could not have been so comprehensively successful without the many calculated steps that preceded it.

The blockade, both in its design and execution, was multi-dimensionally creative. It was a perfect blockade that exploited geographic and geopolitical vulnerabilities to achieve specific and complex objectives in a very short period of time.

This investigative analysis also highlights new questions that require further research, especially:

- How did Azerbaijan, with no previous experience in enacting complex comprehensive sieges, design and manage the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh?

- Did Azerbaijan have complicit partners in the design and execution of the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh?

With the right of return of displaced Artsakhi Armenians still far from secured, the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh continues, for there is still no way to go back home.

###

About the Artsakh Union

The

Artsakh Union, a grassroots civil society organization, was established by Artak Beglaryan following the forced displacement of the Armenians of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) after the genocidal aggression and nine-month-long blockade by Azerbaijan in 2023. Its mission is to advocate for the collective and individual rights of the Artsakh Armenians globally. It is committed to facilitating international justice and accountability and protect the right of return of the historic Armenian community to their ancestral homeland.

About the Zovighian Public Office

The Zovighian Public Office (ZPO) was established in 2015 to serve communities facing crises and crimes of atrocity. We are dedicated to amplifying their voices through research, advocacy, and diplomacy. We are deeply committed to justice and accountability for the Artsakhi Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh.